American; a label revered by enthusiasts of the many modern forms of Jazz. There are conflicting reports as to when Blue Note came into being, but its formation and the recording of its first sessions seem to have taken place in late 1938, and the release of its first record in January 1939. The man behind the label was expatriate German Alfred Lion; according to a retrospective in 'Billboard' if the 16th of January 1999 he was joined in 1941 by another German, Francis Wolff. Wolff was to be responsible for the photographs that graced the distinctive Blue Note album covers, which were designed by Reid Miles. Lion's being drafted into the army led to a break in recording during 1942-43, but Blue Note resumed operations the following year. At first the company concentrated on Boogie Woogie and traditional 'Hot' Jazz, doing some of the groundwork for the revival in Sidney Bechet's fortunes as it did so, but in the late 1940s it embraced Bop with enthusiasm. 'BB' of the 10th of September 1949 made an early reference to the new form, noting that Blue Note was releasing 10" shellac Bop records by Tadd Dameron, Howard McGhee and Thelonius Monk, and the company went on to make other historically important recordings in the early '50s. It issued its first eight albums - 10" ones - in September 1950, five of them being compilations from its successful back catalogue. 'BB' of the 30th of September, breaking the news of the releases, referred to Blue Note as a 'pioneer Hot Jazz indie'. Three years later, 'BB' of the 3rd of October 1953 called Blue Note 'one of the oldest indie Jazz labels in the business' - the oldest being Commodore - and noted approvingly that it had 'kept well abreast of modern sounds' with its 'New Faces - New Sounds' series of albums. By that point the company had releases by the likes of Milt Jackson, Lou Donaldson, Miles Davis, Vic Dickenson, Horace Silver and Dizzy Gillespie in its catalogue.

Blue Note continued to plough its visionary furrow throughout the '50s and into the '60s, recording more artists whose names were to become familiar even to people who weren't Jazz enthusiasts - artists such as Art Blakey, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Cannonball Adderley, Stanley Turrentine and Dexter Gordon. Rudy van Gelder was responsible for the sound of much of the company's output during that perod; his studio technique and engineering skills are reputed to have been as important and revolutionary as the music. Blue Note ventured into a new market in 1957: after six months of trials had met with a 'very enthusiastic' response it put out eleven 45rpm records, aimed at the Juke Box market ('BB', 29th July). 'BB' of the 17th of November 1958 noted that Blue Note would be celebrating its 20th anniversary in January of the following year; later, 'BB' of the 10th of July 1961 referred to Francis Wolff as the company's vice-president. By 1963 'BB' was able to say that Blue Note was in the midst of one of its most successful periods, despite the loss of three of its best-selling artists: Art Blakey, Jimmy Smith and the Three Sound. The article added that new signings had been made in an effort to fill the gap, and that veteran artists were continuing to be developed 'in new formats'. In Herbie Hancock, whose 'Watermelon Man' had been a hit, Blue Note had one of the 'outstanding new talents in Jazz', while Silver, Donaldson and Gordon were 'firmly entrenched', as were Kenny Burrell and Donald Byrd. By that time, the article observed, Blue Note had built up a catalogue 'uniquely representative of all modes of Jazz' ('BB', 11th May 1963).

Alfred Lion continued to keep Blue Note ahead of the game. 'BB' of the 31st of July 1965 quoted him as saying that he was working towards public acceptance of avant-garde Jazz material by gently 'slipping in' that kind of album among the more acceptable material, thus building a foundation for the new music by providing exposure for it. According to the article, despite his enthusiasm for the genre Lion told new artists to 'go slow' when developing an idea rather than 'hitting the public over the head'. The company's continuing success and the richness of its back-catalogue attracted attention, and the following year 'BB' of the 28th of May 1966 announced that Blue Note had been purchased by Liberty Records, with Lion and Wolff being retained as co-division managers under a two-year contract. In an interview with 'BB' of the 16th of July, Lion was confident that with Liberty's nationwide distribution behind the label and a promotional campaign being undertaken, sales would 'spark'. He claimed that the market for 'way out' Jazz was good and was growing steadily, and he underlined the company's policy of not being concerned about commercialism, saying that he believed that something good would sell, either immediately or over the course of time; in support of that he cited the increasing acceptance of Ornette Coleman's records. There was, however, a shift of emphasis shortly afterwards, when the arrival of Liberty's Bernard Blosk as national sales manager led to a campaign aimed at building up Blue Note's presence in the Juke Box market. The Jazz Single line was expanded, singles that had sold well were made more readily available, and a series of 'Little LPs' was launched, the first ten being released in September ('BB', 13th August 1966). Ten months or do later, edited versions of albums were made available to DJs in an attempt to gain increased radio exposure, and a greater emphasis began to be placed on R&B. Reportedly this was merely a response to improved sales in that area over the past few months rather than an attempt to shift the balance of product toward a mass appeal ('BB', 3rd June 1967).

More, and bigger, changes were on the way. The first came in the summer of 1967 when Alfred Lion retired after nearly thirty years leading the company; he seems to have been frustrated by the restrictions involved in dealing with Liberty. His replacement was Mel Fuhrman, previously one of Liberty's regional managers, who was installed as Blue Note's general manager ('BB', 4th November). Another loss was designer Reid Miles, who left around the same time as Lion. After Lion's departure Francis Wolff stopped doing photography for the albums and took over the role of record producer. The second big change came in the Spring of the following year, when Liberty was bought by the Transamerica Corporation, owners of United Artists Records. Being a part of Liberty, Blue Note was included in the deal ('BB', 6th April 1968). Fuhrman remained in charge of the label, but eventually he was given responsibility for United Artists' 'Solid State' Jazz line and the R&B label Minit as well. The final link with the original Blue Note was broken in 1971, with the death of Francis Wolff ('BB', 20th March).

After the death of Wolff, producer George Butler was appointed director of Blue Note ('BB'. 15th May 1971). He went on to produce records for the label into 1977, alongside producing Ferrante & Teicher and Shirley Bassey records for United Artists. 'BB' of the 10th of July 1971 said that Butler's blueprint was to get Blue Note back into the limelight: in order to display its versatility he intended to record a wide spectrum of Jazz, from established forms through the new 'funky' type to mild avant-garde. He was also going to start issuing singles again - there hadn't been any, of late. In an attempt to make Blue Note more commercial and to give it a 'surge ahead' identity he began to supply records to Underground and College radio stations, which the old Blue Note hadn't done. Blue Note's vaults weren't ignored: 1973 saw the launch of a trio of 'A Decade Of Jazz' compilation double-albums ('BB', 3rd October). By November of that year Butler had become Blue Note's president ('BB', 24th November 1973). His approach of 'emphasizing some kind of musical universality' bore fruit: 'BB' of the 13th of July 1974 noted that while the sales figures for Blue Note LPs were usually in the 30,000 to 40,000 range Donald Byrd's 'Black Byrd' album had sold 300,000 copies and the figure was rising. The following week 'BB' of the 20th of July observed that Blue Note was 'breaking the Jazz mold'. It quoted Butler as saying that the Blue Note logo represented avant-garde Jazz to too many stations; thanks to national promotions director Eddie Levine the new approach taken to the Donald Byrd album had worked, but if the label was going to stand tall its records had to cover the musical spectrum. As if to emphasize this, Blue Note had just signed its first white artist, Dom Minasi - Lion and Wolff had set out with the idea that Blue Note ought to be purely 'ethnic'.

Under Butler, Blue Note continued to head in its new direction. 'BB' of the 6th of September 1974 commented that the 'crossover' product had been successful in the States, and the issue of the 8th of February 1975 drew attention to the facts that most of the label's old artists had gone and that new signings were being steered in a more commercial direction. 'BB' of the 13th of September 1975 noted that Blue Note was now referring to Jazz as 'Street Music' as part of its effort to change its image, and that it was selling to Soul outlets as well as its usual Jazz ones. The label was now looking for 'creativity, uniqueness and commerciality' from its artists, whereas the latter had never been a consideration under Alfred Lion. Much of the impetus that had been gained died away after Butler left to join Columbia Records, in the second half of 1977. Two quick changes of ownership for its parent company United Artists Records may not have helped - it was bought by the M&R Music Corporation in April 1978, and then by Capitol / EMI in February 1979. Along with UA's sales, merchandising and A&R staff, current Blue Note chief Eddie Levine departed soon after the purchase by Capitol / EMI, and Blue Note ended the decade in a rather sorry state, dependent on its back-catalogue and with Horace Silver as its only active artist ('BB', 24th March 1979). It was 'in limbo' by 1981, and it languished for a while after that, but happily it was relaunched by EMI in 1985, with enthusiast Bruce Lundvall at the helm, for new recordings as well as reissues. The relaunch succeeded. Under Lundvall appreciation for Blue Note's catalogue became widespread, and a '60th Anniversary' feature in 'BB' of the 16th of January 1999 was able to describe the label as 'currently one of the world's leading Jazz labels', a position it continues to hold.

With regard to Britain, Blue Note never had an independent office here at any point, and until 1970 all of its records were brought in from the States. 'BB' of the 5th of May 1962 reported that Blue Note records were being handled by Ken Lindsay's sixteen-month-old company Central Record Distributors - importing was seen as a better option than sending master tapes over and having pressing done in this country, as it enabled smaller quantities to be dealt with. 'BB' of the 3rd of September 1962 noted that Francis Wolff was in London for talks with CRD. After the loss of independence, imports remained the norm: 'Record Retailer' of the 12th of February 1970 referred to Blue Note's records as being imported to Liberty's warehouse in Wigmore Place. The occasional single was pressed here in the early '70s but Blue Note albums continued to be imported until 1975. 'RR' of the 12th of December 1970 said that the job of handling the imported records was to be handed to EMI Imports, and EMI continued to carry out that task for the next three years, with United Artists' marketing department providing additional promotion from the summer of 1972 onwards ('Music Week', 3rd June). At the end of that time, Blue Note was semi-detached from its parent company, and the responsibilty for importing, promoting and distributing its products was given to Transatlantic ('MW', 8th December 1973) - Transatlantic (q.v.) was an independent company which had experience in importing and promoting American labels. The creation of UA's own sales force in Britain in 1975 enabled that company to take responsibility for Blue Note itself; according to 'MW' of the 30th of August the transition was to take place on the 1st of October. 'BB' of the 6th of September confirmed the development, and added that the parting was amicable. According to a spokesman for Transatlantic, sales of Blue Note albums had risen by some 400% while that firm were handling the label. Finally 'MW' of the 11th of October was able to state that the first Blue Note records via UA were scheduled for release; there were to be some UK pressings but LPs would continue to be mostly imported.

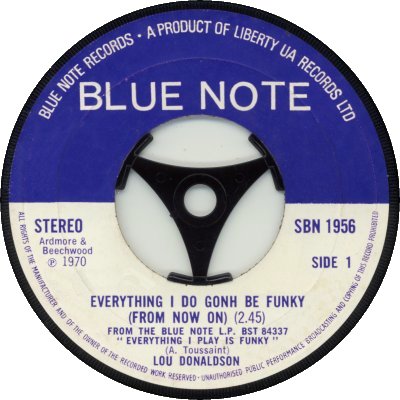

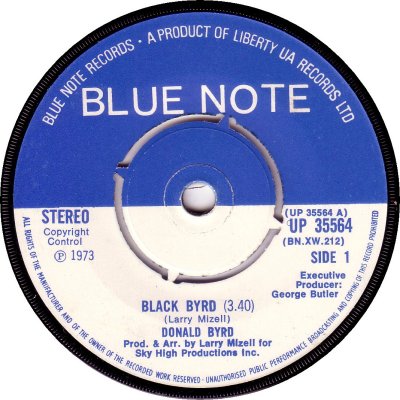

Blue Note was predominantly an album label here in the '60s and '70s, but it did however issue a few singles during the period covered by this site. Unlike its LPs, these were mostly UK pressings. The 'New Singles' leaflets for the Autumn of 1964 gave details of four Blue Note singles, as listed in the discography below, but they were imports. The first proper UK Blue Note single was Lou Donaldson's 'Everything I Do Gohn Be Funky' b/w 'Minor Bash', which came out in 1970 and bore the same catalogue number as the original American issue, SBN-1956. Referring to it as the first Blue Note record to be manufactured in this country, 'RR' of the 18th of July said that the single was due out on the 24th, through Philips. The single was indeed pressed by Philips - as can be seen from the scan (1) it has the large spindle hole peculiar to Philips / Polydor / Phonodisc products in this country - but as Liberty moved from Philips to EMI on the following Monday (the 27th) it was distributed mainly, perhaps solely, by EMI ('BB', 1st August 1970). There had been speculation in 'BB' of the 25th of July that if sales were good enough the LP from which the single was taken might be pressed in the UK, but apparently figures failed to reach the required level. At this point Blue Note seems to have been in need of some attention: 'RR' of the 24th of October observed that it hadn't got a label manager here and that it was being handled by Liberty / United Artists directly. There was a promise of increased promotion for the label in 'Music Week' of the 3rd of June 1972, which reported that the United Artists marketing department was putting more weight behind it. A couple more singles were issued over the course of the following twelve months or so, and again they were UK pressings. Both had the familiar Blue Note label, but their catalogue numbers were taken from United Artists' main UP-35000 series (2).

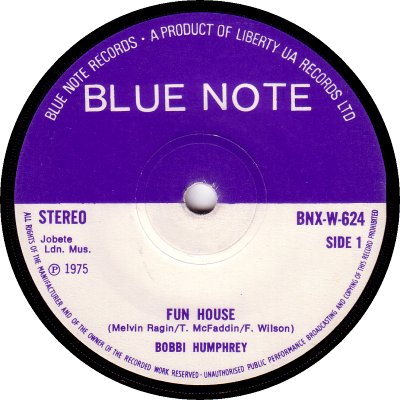

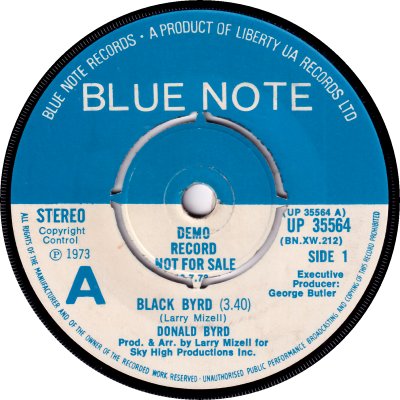

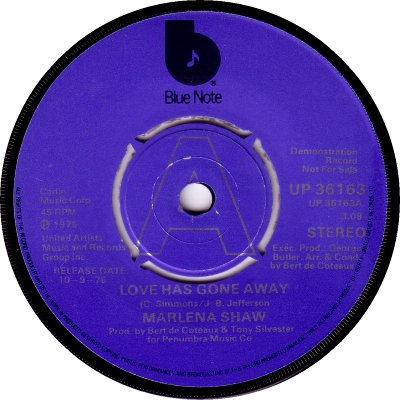

Another couple of blue-and-white-labelled singles came out in 1975, during the Transatlantic period, with catalogue numbers taken from Blue Note's American BNX W-600 series. Both were manufactured by Phonodisc, who were often responsible for Transatlantic's pressings at the time (3). After Blue Note returned to the United Artists fold its singles were initially given their own BNXW-7000 numerical series, along with a new all-blue label (4), which had been used in the USA since 1973. From mid '76, while keeping the same label design, the singles went back to sharing UA's main UP-36000 catalogue series (6). Demo copies, when there were any, had the same sorts of overprinting as did those of United Artists (5, 6). When Blue Note was revived in the mid '80s its label design imitated that of the 78 r.p.m. era. With the exception of the Philips and Transatlantic periods manufacture and distribution of the singles in the '70s were by EMI, as that company handled all the United Artists / Liberty labels. The discography below only covers the 1960s and the 1970s.

Copyright 2006 Robert Lyons.