American, out of New York. CTI - Creed Taylor Incorporated - received its first mention in 'Billboard' of the 10th of June 1967, which noted that A&M had signed a long term production deal with the 'new' company. Taylor had helped to developed the 'Pop-Jazz' label Bethlehem before moving on first to head ABC / Paramount's Jazz label Impulse (q.v.) and then to do the same for MGM's Jazz outlet Verve (q.v.). The article said that he was leaving Verve to set up his own office but that the deal left him free to carry out existing production commitments. It added that his productions were intended to appear on the A&M label with a credit to 'Tayco Sound', but when the first albums appeared they bore a credit to CTI instead. 'BB' of the 24th of June said that the agreement was an attempt by A&M to make a name for itself in the Jazz market, but that the records made under the deal would not be labelled as Jazz; they would be promoted and marketed by the same people who were responsible for handling the company's Pop output.

The arrangement with A&M lasted until the start of the new decade, at which point Taylor launched CTI as a label in its own right. 'BB' of the 28th of February 1970, commenting on the launch, said that the new label would have two separate series, one for Jazz and one for Pop, and added that Taylor was looking for masters, especially soul, rock and country. The 'Pop' direction proved to be short-lived, with the only fruits being a Singer / Songwriter album by Cathy McCord and a Rock one by a band called Flow, and soon CTI began to concentrate on the genre for which it would become well-known. 'Record Retailer' of the 25th of July claimed that a distribution deal had been signed with Philips for the UK and that CTI product would begin to appear with its own label towards the end of that summer, but while Philips did indeed put out a few CTI albums they came out on Philips rather than on CTI itself. The following year CTI gained a subsidiary, Kudu (q.v.). 'BB' of the 31st of July 1971 stated that the new label had been formed in order to showcase the company's more commercial products, and that it would be handling R&B Jazz and Blues Jazz, leaving CTI to feature the 'more experimental and universal' items in its output.

1972 saw both CTI and Kudu making their debut in the UK as labels, via a three-year deal with Pye. 'Music Week' of the 29th of April broke the news of the deal and confirmed that the labels would be given their own identity. The first UK albums came out shortly afterwards, as did the first Kudu single, but it would be a year till the first CTI single appeared - the company's focus was always on LPs. That same year CTI opened a branch in Los Angeles ('BB', 19th February) and then moved its headquarters from Manhattan to New York ('BB', 24th June). July found it in court seeking to prevent a firm called Car Tapes from using a 'CTI' trademark on its products, on the grounds that CTI had been using the trademark on its records since 1967.

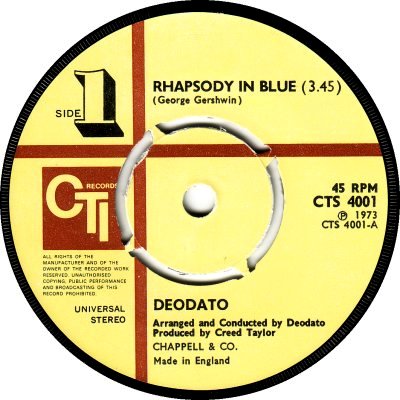

CTI's first UK single, 'Also Sprach Zarathustra' b/w 'Spirit Of Summer' by Deodato (CTS-4000), came out in May 1973, after running into some problems. It had been a hit in America, but according to 'BB' of the 14th of April it was unlikely to be issued in Europe due to objections by the heirs of the composer, Richard Strauss - the piece was out of copyright in the USA but not in Europe. It had been scheduled to be released in Britain on the 1st of February, but had been shelved. Happily the shelving turned out to be only temporary. 'BB' of the 28th of April reported that the ban had been lifted and that the release could go ahead. Pye reckoned that the dispute would cost the single 10% of its sales, but they duly put it out. Somewhat unexpectedly, it repeated its American success and climbed into the Top Ten here, peaking at No.7.

1974 started off in less than encouraging fashion. 'BB' of the 8th of June said that CTI had been 'undergoing financial problems', as a result of which it was negotiating with several companies for a new distribution deal. A fortnight later 'BB' of the 22nd reported that a deal was being agreed with Motown. Motown was to handle sales, promotion, marketing and merchandising; the other details were being settled. As Motown was in the process of widening its musical interests, CTI's arrival was welcome - its Jazz catalogue complemented the Country and Rock that had already been added to Motown's original Soul / Dance genre. CTI settled down into its groove; 'BB' of the 8th of February 1975 commented that it had stuck as closely as any company to its course of blending legitimate tasteful Jazz with elements from R&B, Classical and Funk, and referred to the popular success of Deodato, George Benson, Stanley Turrentine and Esther Philips in the USA. Later in the year an advert in 'BB' of the 5th of September pointed out that CTI and Kudu were responsible for the top three albums in the Jazz charts along with another seven in the Top 40. In less Jazz-friendly Britain the returns were not so encouraging, and 'MW' of the 12th of April 1975 observed that Pye had not renewed its licensing deal with the label - its costs had been covered but there had been no big sellers. A few months later 'MW' of the 19th of July noted that CTI had signed a new agreement, with Polydor. As an aside, 1975 also saw CTI's in-house arranger Bob James becoming the first person other than Creed Taylor to produce a record by a CTI artist.

There was a broadening of CTI's musical interests in 1976. Jerry Wagner, vice-president and general manager, said in 'BB' of the 7th of May that the company was taking a 'Strong left turn' into the fields of R&B and Pop, which could even see the signing of 'Teen rockers' at some point in the future. Kudu and CTI's '5000' album series would be slanted towards these new genres, but the developments would not come at the expense of Jazz. The intention was for Creed Taylor to remain totally involved in signings, A&R and production deals, but the doors would be open to outside producers. Wagner reiterated that CTI saw itself as an album-orientated concern, with singles being used solely as a means of bringing the artists' music to people's attention.

The widening of scope and the company's Chart successes in the States notwithstanding, there were troubled times ahead for CTI. May 1976 saw the company involved in wide-ranging disputes with its distributor, Motown. Agreement was reached, after litigation. Then 1977 delivered a triple whammy, in the shape of three more lawsuits. Motown brought their second one in September; then in October Bob James went to court seeking a temporary ban on CTI distributing the three LPs he had made with the company - apparently he had become disenchanted with CTI as a result of what he considered to be inadequate distribution arrangements and a failure to pay royalties ('BB', 8th October). Finally 'BB' of the 26th of November reported that Grover Washington was suing the company, seeking freedom from recording and publishing ties and asking for $5 million in damages. Other defendants in this last case were CTI-related publishers Three Brothers Music and the Motown Record Company - as part of its separation deal with Motown, CTI had had to agree to Washington joining that company and his Kudu back catalogue going with him.

'BB' of the 8th of July 1978 was able to break the news that the Washington case had been settled out of court, but that same month came yet another lawsuit. This time it was the band Seawind who were suing. They too were seeking to terminate their pact with CTI, and they were asking for $3 million in damages, alleging 'numerous contract violations' which included not paying for the band's first album. Ominously, CTI's legal representatives advised the court that the company was currently unable to pay its debts, and that its saleable assets didn't match the sums that it owed. The following month CBS began to withhold royalty payments on the grounds that CTI hadn't paid its bills for pressing product. Finally, on the 8th of December 1978 CTI filed for bankruptcy, as mentioned in 'BB' of the 11th of August 1979. That same issue of 'BB' revealed that judgement had gone in favour of Bob James in the case mentioned above: his masters and unissued material were to be returned to him on his paying CTI the sum of $25,000. The judge who gave the verdict was the same one who was by that time handling the reorganization of CTI under the Bankruptcy Act.

CTI struggled to find a way forward. In the second half of the '70s it had lost some of its best-selling artists to other companies - in the 1980s it was to sue Warner Brothers over the circumstances of George Benson's 1975 move to that company and for the alleged failure of the artist to deliver two albums to CTI under the terms of that move - and in 1979 it lost its back-catalogue, which went to Columbia as part of a new distribution deal. It tried a new tack, introducing a series of 12" singles under the name '12-Inch Rulers' ('BB', 14th March 1979), but the venture proved unsuccessful. 'BB' of the 11th of August 1979 had the sad task of announcing that there had been fourteen more redundancies, leaving the company to operate with a skeleton staff of six. There was however something of an up-turn in the early '80s: 'BB' of the 3rd of July 1982 was able to state that, a year after carrying out a reorganization, CTI had met its sales projections and had resolved its legal and financial difficulties. Under vice-president and general manager Vic Chirumbolo it was also 'beefing up' its staff. John Taylor, Creed's son, was serving as sales executive. 'BB' of the 21st of July added that the company was reviving its Gospel label, Salvation, which would rejoin the CTI, Kudu and Three Brothers labels. There appears to have been little new material issued until 1990, however, and that 1990 revival was not a success. An attempt by Creed Taylor to buy back CTI's catalogue failed; the masters stayed with Columbia, and are now - with the exception of the Washington, James and Seawind material - owned by Sony.

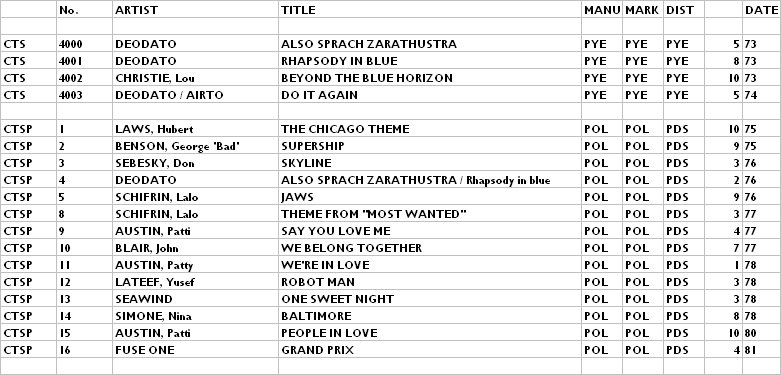

In Britain a few Creed Taylor productions for A&M appeared on A&M in the late '60s, with a couple of CTI albums following on Philips in 1970. As stated above, CTI and its subsidiary Kudu were initially launched as labels in their own right by Pye in May 1972. The label design (1) was the same as that of its American counterpart except that it lacked Creed Taylor's signature, which featured on American records. Following the move to Polydor, Phonodisc's customary injection moulded labels were used. These were generally fawn- or concrete-coloured, but the occasional orange one (4) can be found. The only minor change in that design came in the spring of 1976, when the small 'A' at 2 o'clock (2) grew substantially in size (3). In the Pye era promo copies were marked with a medium-sized solid 'A' and the usual text, all in silver print (5); there were no promo markings during the Polydor years. Numbering for singles began in a CTS-4000 series with Pye; this changed to CT SP-000 after the move to Polydor, though the first '0' was later dropped. Polydor's usual practise was to use all-numerical catalogue numbers, but according to 'BB' (21st January 1978) as part of the licensing deal CTI had stipulated that alphabetical prefixes were to be used for its labels. In addition to Deodato's 'Also Sprach Zarathustra' CTI got a couple more singles into the Charts: George "Bad" Benson's 'Supership' b/w 'My Latin Brother' (CT SP-002: 9/75) stalled at No.30, but Lalo Schifrin's version of the 'Jaws' theme b/w 'Quiet Village' (CT SP-005; 9/76) improved on that, reaching the No.14 spot. In addition Kudu gave the company its best placing when Esther Phillips took 'What A Difference A Day Made' b/w 'Turn Around, Look At Me' (KUDU-925; 9/75) to the No.6 position. Another Kudu single, 'Could Heaven Ever Be Like This' b/w 'Turn This Mutha Out' by Idris Muhammad (KUDU-935; 8/77) edged into the Top 50 but got no higher than No.42.

Copyright 2006 Robert Lyons.