The record label of the Dutch electrical firm of the same name. Philips received an early mention in 'Billboard' of the 6th of September 1952, which said that EMI executives Leonard Smith and Norman Newell had resigned and were expected to join Philips when it started its 'disk activities' in England in the autumn. The article also said that Philips was to represent American Columbia in this country at the start of the new year, the deal supplanting Columbia's previous one with EMI. Preparations for the launch were 'progressing rapidly' but no date had been set. In the event both Smith and Newell played major parts in getting the new operation up and running. Looking back, 'Music Week' of the 26th of February 1972 credited Smith with arranging A&R, setting a pressing facility up and arranging for distribution, as well as with looking after sales, advertising and promotion. 'BB' of the 24th of January 1953 was able to report that the first Philips records were due to come on the market the following week. The company had established a pressing plant at Walthamstow (it appears to have gone on to handle distribution as well) and had signed several British artists, including Gracie Fields, David Hughes, Gary Miller and Flanagan & Allen, with the intention of supplementing the material that was to come from American Columbia. 'BB' of the 24th of October added that the new company was 'moving at a fast clip' under A&R man Newell, and the issue of the 6th of February 1954 was able to provide confirmation of that. In its first year of operation Philips had sold more than four million records, including half-a-million copies of Frankie Laine's 'I Believe' - Laine went on to hit the Charts repeatedly during the '50s, registering thirteen Top Ten hits as well as four Number Ones. Newell returned to EMI in 1954 but Philips continued to prosper.

Philips came somewhat late to the party as far as 7" 45rpm singles are concerned, though it made some 7" 78rpm ones in 1952 in an attempt to capitalize on the abundance of 78rpm record players ('BB', 4th October 1952). Its singles mainly came out in the common 10" 78rpm format until December 1957, when its first commercially available 7" singles came on the market - it had introduced its first 7" vinyl records in 1955, but they were all EPs. In addition, early 1957 had seen the appearance of mainly large-spindle-holed singles, but they were solely intended for juke box use; issue copies were all 10" 78s. The company continued to release 78s until the autumn of 1959. 45rpm and 78rpm singles shared the same catalogue numbers, in a PB-100 series, with 45s being given a '45' prefix, logically enough. From April 1960, after the demise of the 78rpm format, that prefix was abandoned and the 45s had the PBs - which by that time were in the PB-1000s - to themselves.

The start of 1958 saw Philips launching a new label, Fontana (q.v.). It was run by Jack Baverstock and was initially intended to be primarily an outlet for material from American Columbia's 'Epic' subsidiary. However, American Columbia were anxious to have their own label in the UK, which would have left both Philips and Fontana without a source of American material. As a consequence the early '60s saw Philips looking to buy an American company. Negotiations with the Mercury Record Corporation took place, and as a result 'BB' of the 26th of June 1961 was able to reveal that the acquisition had been successfully carried out. This gave the green light to the formation of the American Columbia's British label 'CBS', which was handled by Philips initially. As Mercury had a deal with EMI in Britain Philips was unable to take over manufacture and distribution of its new purchase here until that agreement expired, which it did at the start of 1964. In addition Philips carried out its first licensing deal, acquiring the rights to another American company, Vanguard (q.v.), and to its entire back catalogue, which covered a wide range of Folk, Jazz and Classical music ('BB', 27th January 1962). Philips's ambitions didn't stop there, and in June 1962 it joined forces with Deutsche Grammophon, parent companies Philips Gloeilampenfevriehen of Holland and Siemens & Halske of Germany buying 50% of each other's record business to form the Grammophon Philips Group, DG/PPI. Philips and DGG/Polydor were to go on operating as independent companies under the new arrangement.

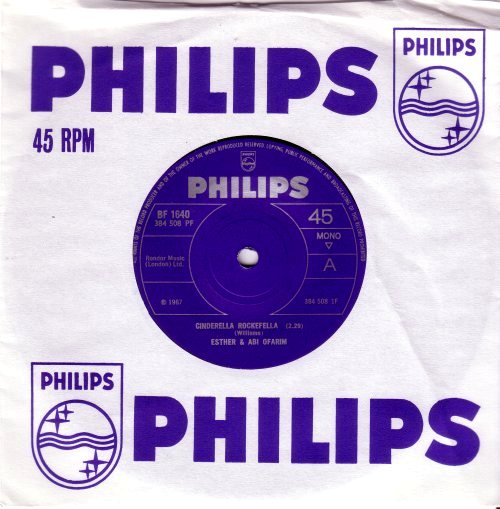

Philips continued to flourish in the early 1960s, with the likes of Marty Wilde and Frankie Vaughan continuing their runs of hits into the new decade. New hit artists came on the scene, some of whom saw the company frequently in the Charts throughout that decade: Dusty Springfield was the most consistent, scoring seventeen times between 1963 and 1970, but the Walker Brothers were also big contributors, registering nine times between 1965 and 1967 and adding five more successes as solo artists afterwards. The Four Seasons, Blue Mink, Roger Miller and Esther & Abi Ofarim also provided several hits each during that period. The loss of CBS and its artist roster in March 1965 was a blow - CBS opted for independence, buying the Oriole company as a basis for its operations - but Philips responded by linking up with independent producers and launching new labels. Andrew Loog Oldham's 'Immediate' (q.v.) was the first, appearing in August of that year; its first release, 'Hang On Sloopy' b/w 'I Can't Explain It' (IM-001; 8/65) provided an immediate reward by reaching the No.5 spot, and runs of hits by Chris Farlowe, P. P. Arnold, and, more impressively, the Small Faces confirmed Immediate as a commercial success. The Planet label, run by Shel Talmy, appeared some four months later ('BB', 20th November 1965) and made less of an impression, but it scored minor hits with a couple of singles by The Creation.

A third independent was launched via Philips the following year: Larry Page's 'Page One' (q.v.). The initial agreement between Philips and the Page One production company called for the latter to supply three singles per month for release on the Fontana label ('BB', 16th April 1966), but 'Wild Thing' b/w 'From Home' by The Troggs (TF-689, 4/66) soared to No.2 in the Charts, and the band's follow-up, 'With A Girl Like You' b/w 'I Want You' (TF-717; 7/66), went all the way to No.1. Presumably encouraged by this, Page One made its debut as a label in its own right shortly afterwards ('BB', 17th September). It enjoyed a No.2 with its first release, another Troggs single, 'I Can't Control Myself' b/w 'Gonna Make You' (POF-001; 9/66), and the group went on to provide six more Chart entries. Other hits were to come from Vanity Fare, the Plastic Penny and Deep Feeling. All things considered, Philips could claim to have recovered from the loss of CBS more than adequately. Looking back at 1966 in 'BB' of the 17th of December, managing director Philip Gould was able to point to thirty-five singles having sold over 100,000 copies and twenty which sold over 500,000 (sales of direct exports included). Singles production had doubled, Philips's share of the UK record market had gone up by 9%, and the artist roster boasted internationally popular acts such as The Spencer Davis Group, The Mindbenders, Joan Baez, The Troggs, and latterly Manfred Mann and Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich. In addition, Philips was to take over the distribution of Island Records and its associated labels, from the start of the New Year.

There were more developments to come, in the late '60s. After leaving EMI in the summer of 1967 and becoming independent, Liberty turned to Philips for manufacture and distribution ('BB', 17th June), which meant that Philips handled all of Creedence Clearwater Revival's big hits of 1969-70. Vanguard was finally awarded label status in 1968 ('BB', 10th April 1968), though that honour wasn't extended to its singles until early the following year ('BB', 29th January 1969), and Larry Page's 'Penny Farthing' label (q.v.) joined the growing Philips stable in the summer of 1969 via a pressing and distribution deal ('BB', 23rd August). Another arrival was an in-house outlet for 'progressive' music, Vertigo (q.v.), which came on the scene in November 1969. It didn't make a great impact at first but it went on to house some hugely successful acts over the following decades. Another important step was the formation of Phonodisc in 1969. Phonodisc was jointly owned by Philips and Polydor and was intended to serve as a distributor for the records of both companies, including their associated and licensed labels - Philips had begun to distribute its own records directly in March 1965. 'Record Retailer' of the 10th of April noted that it had been registered as a UK company; the issue of the following week observed that the process of appointing management and directors was under way, and that premises were being sought and staff recruited. A location in Ilford was found, and the operation got under way. 'RR' of the 14th of March 1970 mentioned in passing that Phonodisc had been at work for twelve months, while the issue of the 31st of July 1971 described it as 'An experiment by two international groups entering into a distribution company'. The experiment proved to be a successful one, despite a temporary hiatus in the spring of 1970 when faulty computer programming led to dealers' orders running into what 'RR' of the 23rd of May described as 'six weeks of chaos'.

Several more companies came on board in 1970. Some - Nashville, Tangerine and Trend - proved short-lived and didn't make much of an impression, but Soul label Avco Embassy (later just 'Avco', and later still 'H&L') not only boosted Philips's credentials in that field but also provided a generous supply of Chart hits. Sixteen came from The Stylistics, including nine Top 10 entries and a solitary No.1, 'Can't Give You Anything' b/w 'I'd Rather Be Hurt By You' (6105-039; 7/75). Limmie & The Family Cookin' also scored more than once, as did Van McCoy, both acts featuring in the Top 5 twice. Less spectacularly successful but notable in its own way was Philips's licensing of the legendary Sun label, from Memphis, which enabled it to reissue classic material from the likes of Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins. Sun's stable-mate, SSS International, came with it, albeit to no great effect.

There were further arrivals in 1971. Page One's 'progressive' labels Nepentha and Page International came and went fairly quickly, in the case of the former leaving behind some very collectable albums and singles. Carnaby moved over from Pye, but was no more successful after the move than it had been before it. A licensing agreement with American company GRT made more of an impact, as it brought the Chess, Janus and Westbound labels on board ('BB', 31st July). Chess was soon to provide a No.1 in the form of Chuck Berry's novelty 'My Ding-A-Ling' b/w 'Let's Boogie' (6145-019; 9/72), and Janus supplied another novelty No.1 with 'The Streak' b/w 'You've Got The Music Inside' by Ray Stevens (6146-201; 5/74). Stevens also registered three lesser hits, and The Detroit Emeralds scored on both Janus and Westbound.

Away from the matter of new licensing agreements, 'Billboard' of the 8th of May 1971 revealed that Philips and DGG had created another new company, Polygram, to control activities carried out by them and by their subsidiaries. It was to have two divisions: one in Germany and one in Holland. In addition, and importantly, the title 'Philips Records' was to be phased out and replaced by 'Phonogram'. 'RR' of the same date confirmed this but added that there were no plans to drop the Philips label. More immediately relevant to the UK, 'RR' of the 9th of October announced that the Philips pressing plant - which had come under the Phonodisc umbrella by then - was experimenting with 'painted labels', a process invented by French company SFP. A specially adapted injection moulding machine was being used in the process, and the first records to be pressed would be 'Never Ending Song Of Love' b/w 'Cincinnati' (6006-125) by The New Seekers, on Philips, and Slade's 'Coz I Luv You' b/w 'My Life Is Natural' (2058-155), on Polydor. 'BB' agreed with regard to the New Seekers single but said that 'Leap Up And Down' b/w 'How You Gonna Tell Me' by St. Cecelia (2058-104) would be pressed at the same time, with the Slade record following a week later. There is, however, no sign of the St. Cecelia disc in injection moulded form, so it may well have been spared. This experiment, too, turned out to be a success, and in 1973 'painted' labels replaced paper ones for the majority of Phonogram and Polydor singles. On an aesthetic level, however, the change was regrettable, as it led to colourful and adventurous label designs being replaced by ones that were uniform and sometimes stodgy - see 'SSS International' for a prime example. As an aside, the Phonodisc pressing plant eventually underwent a change of name, to Polygram Record Services, in June 1979 ('Music Week', 16th June).

Companies new and old continued to link up with Phonogram. The remainder of the decade saw the arrival and sometimes the departure of Tiffany, WWA, Fresh Air, GM (all 1973), All Platinum (1974), Charisma, Vulcan, Sire (1975), Bang, Ensign (1976), Mountain (1977), Lollipop, Rocket (1978), and I-Spy (1979) (q.v. all). Some were to enjoy big Singles Chart successes: Charisma with Genesis and their ex-member Peter Gabriel, Sire with The Undertones, and Ensign with The Boomtown Rats. Rocket of course brought Elton John into the fold. In addition to the various licensing deals with Phonogram, Arista and Chrysalis both made pressing and distribution deals with Phonodisc, effective from the 1st of July 1977. According to 'Music Week' of the 25th of July, it was the first time that any independent companies had signed up with Phonodisc direct rather than through Phonogram or Polydor. Those deals, too, proved hugely successful: Arista scored repeatedly with Barry Manilow and with Showaddywaddy, the latter providing seven straight Top 5 singles and seven lesser hits after the move to Phonogram; while Chrysalis's post-move Chart regulars included Leo Sayer, U.F.O., Generation X, and especially Blondie - alongside several lesser hits Blondie registered five No.1s and four Top 5 entries over the course of four years. In addition, an association between Chrysalis and 2-Tone meant that Phonodisc was to share some of the fruits of the late '70s / early '80s 2-Tone boom. As well as manufacturing for these companies, Phonodisc undertook contract pressing and custom pressing work for other companies, both major and minor - see 'Stag Music' for an example.

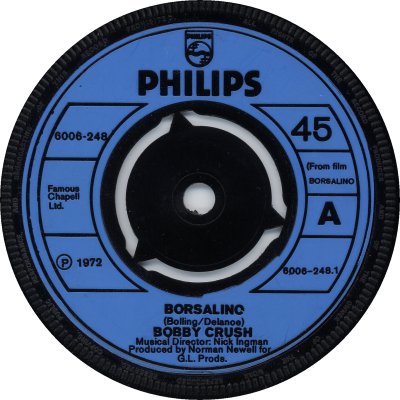

Despite several of its associated labels doing well, some of them spectacularly so, the 1970s turned out to be a relatively poor time for Philips as a label in its own right. There were however several bright spots. Vocal duo Peters & Lee made a sizeable contribution during 1973-76, starting with a No.1 in 'Welcome Home' b/w 'Can't Keep My Mind On The Game' (6006-307; 5/73) and adding four lesser successes. Val Doonican registered once in 1971 and once in 1973, and in addition there were hits by Lobo (1971), Bobby Crush (1972) and Brownsville Station (1974). That said, the Philips label lacked a regular big-selling singles act. Oddly, in the late '60s the company had put out singles by three artists who turned out to be among the best-selling of the '70s: Elton John had two out on Philips in 1968 / 69 and Mud two in 1969 / 70, all of which failed to dent the Charts. David Bowie did better, his 'Space Oddity' b/w 'Wide Eyed Boy From Freecloud' (BF-1801; 7/69) hitting the No.5 spot. Three subsequent singles by Bowie, on the Philips-owned Mercury label, were far less successful and now sell for three-figure sums. 'MW' of the 4th of October 1975 reported that there were plans to alter Philips's image as a MOR label, but the next of their artists to strike paydirt, Demis Roussos, came emphatically under that category. He had a run of six hits from 1975 to 1977, and he too enjoyed a No.1, in the form of a four-track EP, 'The Roussos Phenomenon' (DEMIS-001; 6/76). During the second half of the '70s there were occasionally other successes: Chris Hill hit the No.10 spot twice with novelty Christmas songs in 1975 and 1976, 5000 Volts got into the Top Ten twice in 1975-76, and Santa Esmeralda squeezed into the Top 50 late in 1977. Early 1978 provided a couple more hits with Terry Wogan's version of 'The Floral Dance' b/w 'Old Rockin' Chair' (6006-592; 12/77) and a patriotic EP of Scottish songs by Sydney Devine (SCOT-1; 2/78), but they were the last. Not counting a series of reissues, 'Classic Cuts', there were only five 7" releases in 1980, and from then until 1990 the Philips label was only seen every so often on 7" records, mostly on singles by Nana Mouskouri.

As outlined above, Philips was a little slow to change over from 78 rpm to 45 rpm records. Their first series of 45s, intended for juke box use only, were numbered in the JK-1000s and their labels bore the appropriate marking (1). As far as the main popular series is concerned, catalogue numbers started at PB-100 in the 78 rpm era. They appeared on the right-hand side of the label; there was an equally large six-figure number, with a 'BF' suffix, on the left-hand side, which was an international reference number. The PB-100s reached PB-1200s by April 1962, at which point they were dropped, the six-figure numbers being used instead. The main series was 326500-BF, but there were others such as 304000-BF and 324900-BF, which contained material from different sources. This scheme of things lasted for roughly a year. In April 1963 the old numbering was re-adopted, starting in the 1200s where it had left off, but the 'BF' was retained, this time as a prefix. This time around the numbers were on the left-hand side - the six-figure numbers remained, but were in much smaller print. In April 1970, as reported in 'Record Retailer' of the 4th of that month, Philips abandoned its prefix / number system and started issuing singles with seven-digit catalogue numbers, in line with other group members worldwide, the first number of the seven being '6'; the other labels associated with Philips did the same.

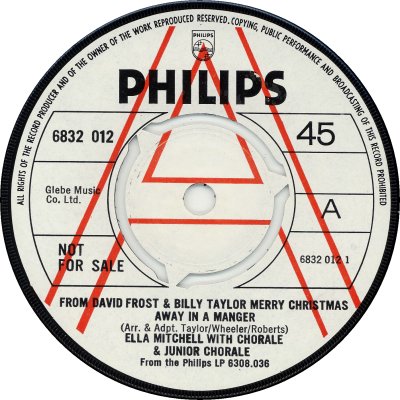

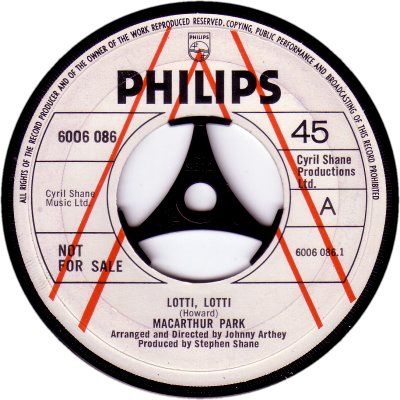

To turn to those seven-figure numbers for a few moments, a trawl of the net suggests that the main Philips singles series in this country was the 6006-000s, which denoted material originating with the British office. Many other countries seem to have had blocks devoted to records for which their offices were responsible. Examples that can be found on singles released in the UK included 6003 (from Germany), 6009, 6042 and 6118 (France), 6012 (The Netherlands), 6079 (America), 6015 (Sweden), 6019 (Denmark), 6021 (Belgium), 6025 (Italy), 6031 (Portugal), and 6037 (Australia). The 6000s and 6198s appear to have been for tracks licensed from various sources, while a short 6113 series featured material from Strawberry Studios. The 6028s seem to have been divided between Switzerland and Val Doonican, for some reason, while the 6073s were split between several sources, mostly American companies - the 6073-000s were from Uni, 6073-100s and 150s from Evolution, and the 6073-250s from producers Cashman & West; the 6073-200s featured material from British company B&C, which was licensed for issue abroad. The 6168s seem to have been an outlet for old material from the Philips vaults, and the 6832s were promo-only items. The 6176es appear to featured tracks produced in France by André Chappelle. Finally, the 6051s seem to have been produced 'in house' by Philips's American branch. In addition most of Philips's licensed labels in the UK had their own prefixes and catalogue numbers. 'MW' of the 24th of December 1977 claimed that Phonogram was considering changing back to the 'letters and numbers' style of numbers, but that if the change happened at all it would be 'Later rather than sooner'. A trial had been made with the 'Roussos Phenomenon' EP mentioned above. In the event a few others followed suit, but in the end the idea of changing was abandoned.

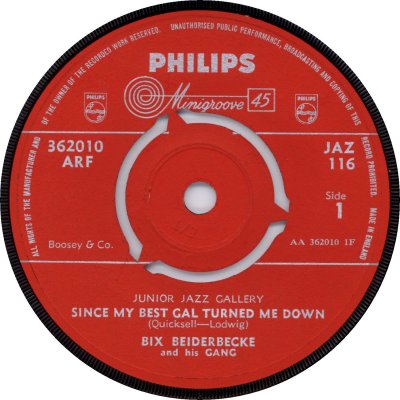

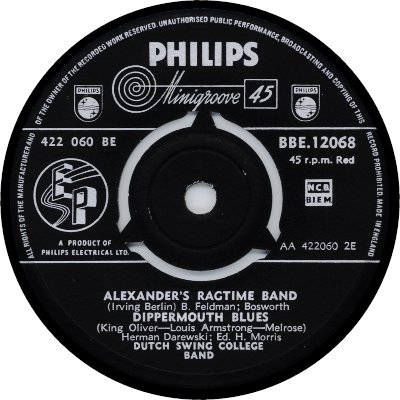

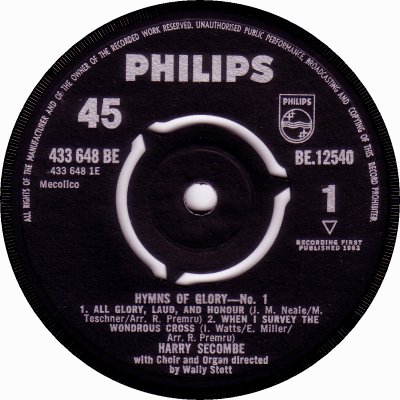

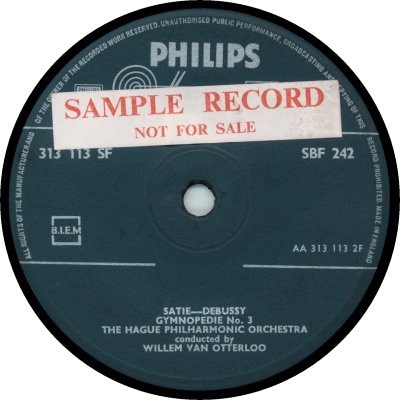

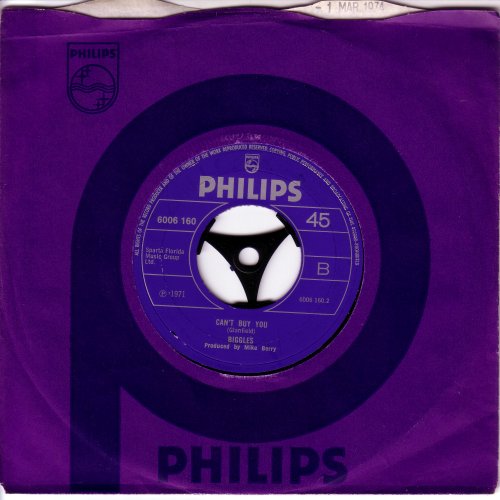

Philips's main series of singles always had blue labels. As far as 7" labels are concerned, the company name was in comparatively small print at first and a process called 'Minigroove' was given prominence (2); from January / February 1962 the 'Minigroove' disappeared and the name grew slightly (3). The name grew again in June 1964, and a grid of lines appeared on the label (4); this design remained essentially unchanged into the early '70s, though the 'Recording first published' at 8 o'clock was replaced by a 'P' in a circle in February 1966 (5). The kind of dinking which results in three prongs (as shown in many of the scans above) appears to have been peculiar to the Polydor and Philips companies, as were the rather graceful triangular 'spiders' which were supplied with factory-dinked singles (6) - it was common in the early '70s for singles in the Polydor and Philips family labels to have their centres removed before they left the factory. Singles with no perforations were relatively rare and tended to be copies of Chart hits, though this wasn't always the case. Phonodisc's own solid-centre pressings had a kind of shallow inverted basin around the spindle hole (7). Singles with four prongs were custom pressings, again usually of hits - the example shown was made by CBS (8).

The first injection moulded labels appeared in 1971, and had the same trio of dinking perforations that the old paper label had had. At this stage singles could be found in either paper-labelled or injection moulded form, but injection moulding seems to have been reserved for hit singles initially. At first the 'prohibitions' around the label's edge were inside the outer ring (9) or both outside it and inside it (10), but they soon migrated outside it (11). As stated above, in 1973 injection moulded singles became the norm. Most came with solid centres (12) but some had large spindle holes and three-pronged 'spiders'; injection moulded singles with 'BF' prefixes are reissues from the mid '70s (13). Usually injection moulded singles were coloured blue, but occasionally yellow-green (14) silver (15) or beige (16) paint was used; thanks to Robert Bowes for the scan of the beige one. Football records led to a couple of other colours being used: a red label graced a tribute single to Manchester United F. C. (17), while a West Ham song was coloured what I suppose was intended to be metallic 'claret' (18). Paper labels appeared every now and again during the injection moulded era as a result of contract pressings done by other firms. The example shown (19) was manufactured by Pye.

The late '50s and the very early '60s saw a 'Musical Gems' series of Classical singles, which had sea-green labels and their own SBF-100 numbers (20). Jazz music briefly had its own red-labelled 'Junior Jazz Series' of singles, numbered in the JAZ-100s (21). The main series of EPs in the '50s (22) and early '60s had black labels and numbers in the BBE-12000s. There were two series of Classical EPs, one of which had green labels and NBE-11000 numbers (24), the other purple labels and numbers in the ABE-10000s (25). The Pop EPs underwent the same kind of number-change in 1962-63 as the singles did, being numbered in the 433600-BFs for that period; they then reverted to the old 12000 numbers but had a 'BE' prefix instead of the old 'BBE' one (23). The advent of stereo saw two more sets of numbers, SBBE-9000 for Popular EPs and SABE-2000 for Classical ones; the labels were marked 'Hi-Fi-Stereo' (26).

Records intended for demonstration purposes had white labels initially, which could be plain (27) or have the details handwritten or printed on them (28), but 'Sample Record' stickers were also used from early on, being applied to stock copies (29, 30). The white label demos disappeared in late 1960, leaving only the stickered kind; these gained an 'A' sticker early in 1962 (31). From around the middle of 1965 into the following year the stickers seem to have been replaced with a rough yellow handstamp reading 'Sample not for sale' - the example shown (32) hasn't been stamped very well. 1969 saw the reintroduction of dedicated promo labels: they were white with a large hollow red 'A' (33, 34). When promo labels were finally abandoned, in the summer of 1971, they were replaced very briefly by another kind of 'Sample Record' sticker (35).

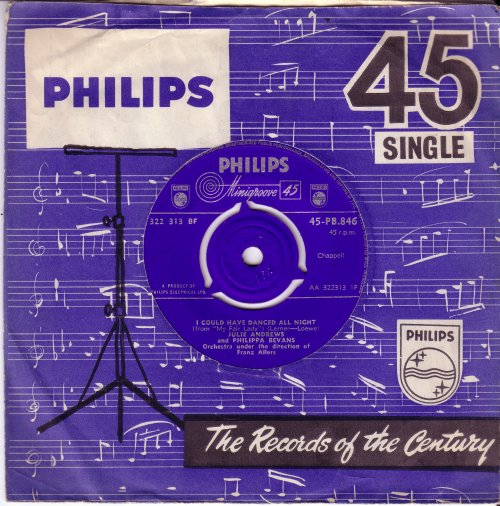

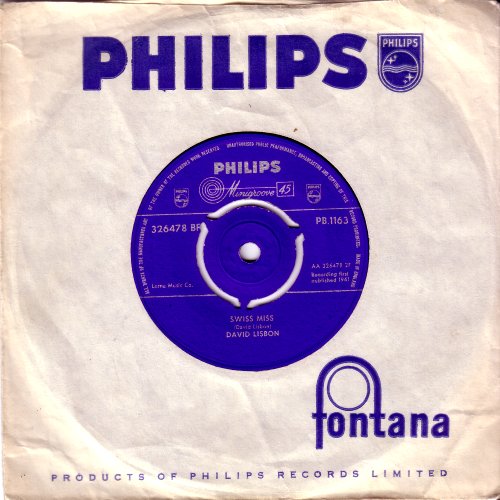

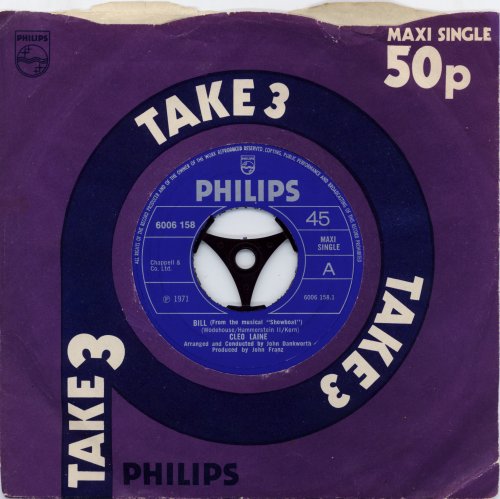

Turning to company sleeves, Philips went through several designs from the '50s to the end of the '70s. The first, a white one with the company's name in a box (36), came and went in 1958. Its successor, which was blue with a picture of a music stand (37) lasted from 1958 into 1960. A white sleeve with the names of Philips and Fontana on it (38) served for both of those labels from 1960 till the end of 1962, at which point one with the company's name and logo on it twice was adopted (39). This proved longer lasting, surviving into 1970. From 1970 into 1974 a more 'with it' design in purple and blue was used (40). 1974 saw the introduction of a corporate Phonogram sleeve with multiple boxed logos; this housed all of the company's labels including Philips (42). The 'boxes' sleeve was replaced by a black-on-red one in 1979 - for my money it didn't go particularly well with the blue Philips labels (43). An occasional 'Take 3' series of three-track EPs was launched in 1971 and had its own particular sleeve (41). The discography below only covers the 1970s.

Copyright 2008 Robert Lyons.