American, out of Los Angeles. 'Billboard' of the 26th of February 1972 broke the news that Wes Farrell, who it called one of the most successful producers over the past five years, was to launch his own label. As yet unnamed it would be handled by RCA. Buzz Wilbourne had been slated as the head of the new label. According to the article the Wes Farrell Organization was already involved in production, music publishing, management and TV and radio commercials; Farrell himself was currently responsible for the recordings of TV's The Partridge Family as a whole and its member David Cassidy. 'BB' of the 4th of March was able to put a name to the new label, Chelsea, and to reveal that discussions with RCA were taking place about its first single. That first single, 'Daddy Don't You Walk So Fast', by Wayne Newton, duly appeared, and it gave Chelsea a flying start - 'BB' of the 29th of July was able to report that it had given the sixteen-week-old label its first gold record. The success led to legal spats with one of Newton's previous labels, MGM: Chelsea took them to court to prevent them using the word 'Daddy' on a repackaged collection of old material and thereby giving the impression that the hit song was among those old recordings ('BB', 10th June). MGM came back with a lawsuit of its own, one of its allegations being that Newton had broken an agreement to record 'Daddy' while he was with them.

Chelsea's good start continued, and its aims began to widen. 'BB' of the 25th of November reported that after enjoying success with its first four singles over the course of eight months the company intended to open a production and music publishing office in London under the umbrella of 'Farrell Entertainment' - the companies involved would be Coral Rock Productions and Coral Rock Music. It was also looking to buy masters from outside producers. In passing, Farrell was quoted as saying that the roots of Chelsea's success lay in putting out few records but making sure that their quality was high. Towards the end of the year the company gained an unlikely but ultimately successful recruit when it signed Lulu worldwide ('BB', 23rd December).

In 1973 the Wes Farrell Organization launched a second label, Roxbury. According to Farrell, as quoted in 'BB' of the 29th of September the intention was to allow the promotions force to concentrate more heavily on individual artists. By that time Chelsea had had hits in several fields: 'soft Soul' with the group New York City, MOR with Wayne Newton, and contemporary Pop / Rock with Austin Roberts. A couple of months after Roxbury's launch 'BB' of the 19th of November stated that the new label was intended to be an outlet for 'heavily contemporary acts', but it seems to have evolved more or less into a vehicle for Disco / R&B material. In the final month of the year Farrell offered some advice on how to run a successful record company: never copy other people's successes and don't follow trends.

The summer of 1974 saw Chelsea splitting with RCA and turning to independent companies for distribution ('BB', 22nd June). Shortly afterwards 'BB' of the 6th of July noted that the Chelsea and Roxbury labels had been 'revamped', presumably for the new beginning - the label designs remained basically the same but the colours and catalogue numbers changed. In September the Wes Farrell Organization shifted the business side of its affairs to New York, covering accounting, sales and royalties. The Los Angeles office continued to deal with sales and promotion for both Chelsea and Roxbury ('BB', 29th September). Another development, late in the year, was the release of Chelsea's first Country record, 'You're The One' by Jerry Inman ('BB', 2nd November). The venture seems to have been short lived.

There were more hits in 1975 including 'Sky High' by Jigsaw, which originated with UK company Belsize Productions. 'BB' of the 14th of July observed that Chelsea had been enjoying success in Britain as well, with seven hits from sixteen releases thus far. In the autumn Farrell told 'Music Week' of the 4th of October that diversity was one of Chelsea's policies, and that his company wouldn't sign an artist who could be compared with any other. In 1976, however, the hits appear to have dwindled; the 'Inside Track' column of 'BB' of the 27th of November was moved to speculate that Farrell might be planning to 'unload' Chelsea and concentrate on production and publishing. In contradiction to this, 'BB' of the 22nd of January 1977 was told that the company had expansion plans - they were looking to increase the numbers of in-house and field staff, sign new acts and look for more overseas licensors. A new emphasis on R&B and Gospel was in the offing, as was the beefing-up of Chelsea's London division, and a doubling of the number of releases was intended. One of the aims was to develop 'lasting performers' and become an albums label rather than a singles one, which it had been till that point.

Sadly the Wes Farrell Organization seems to have run into financial difficulties before the plans got very far. 'BB' of the 18th of June told its readers that the Organization had sold all of its copyrights to a firm called the Entertainment Co. Music Group, which was to have first refusal of new works for the following three years. Then in October, in the UK, Chelsea sued Pye for alleged failure to pay advance royalties or to manufacture records according to their agreement - Chelsea had switched from Polydor to Pye towards the end of 1976. Finally 'BB' of the 12th of November 1977 announced that Chelsea and the Wes Farrell Group as a whole had launched a 'Major refinement program'. 80% of the staff had gone, along with 50% of the artists. Chelsea president Steve Beddel said that the aim was to go back to being a small record company, featuring artists who could perform and write. The 'refinement' doesn't seem to have done much to revive Chelsea's fortunes, as its releases of the previous July turned out to be its last - Roxbury had been shelved a year or so earlier. 1978 brought a lawsuit from manufacturing company Shelley Products, alleging $27,000 in unpaid bills dating back to October 1977 ('BB', 4th February). Soon afterwards artist Rick Springfield sued, claiming that payments owed to him had not been made. He alleged insolvency, wanted the masters that he had made while with Chelsea returned, and his pact with the company and with Farrell declared invalid ('BB', 25th March). That appears to have been the final reference to Chelsea in 'BB'.

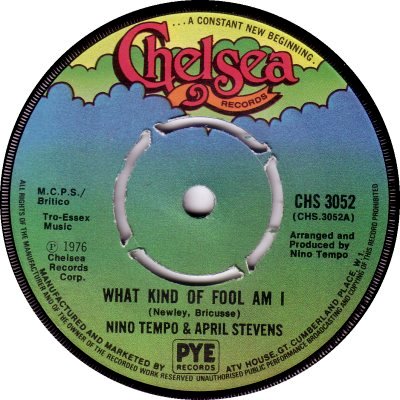

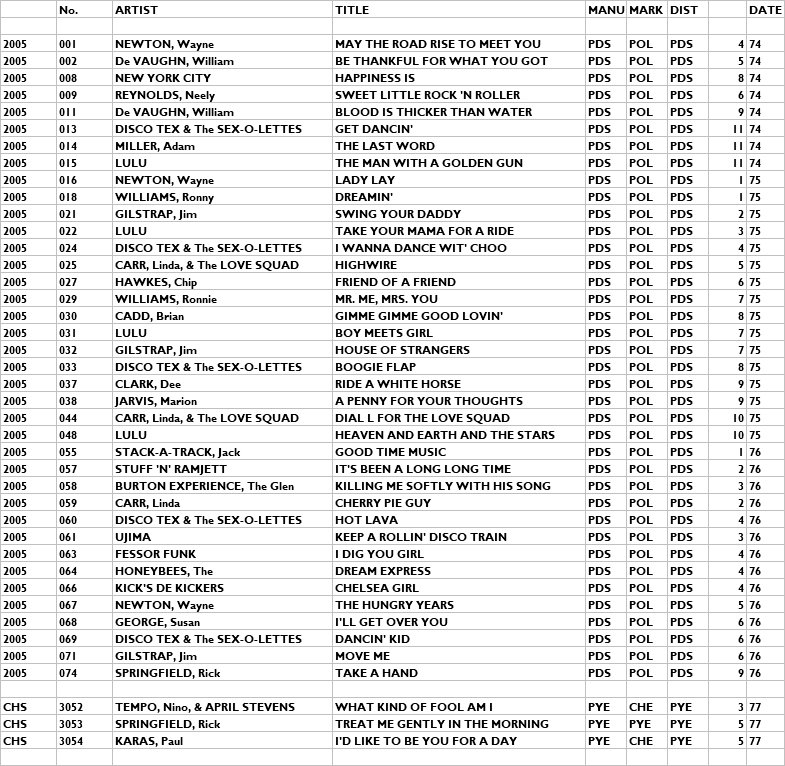

As an actual label, Chelsea got going somewhat later in the UK than in the USA. At first, in a reflection of the relationship in America, the company's products came out on RCA with an originating credit to Chelsea. Then in November 1973 'MW' revealed that Chelsea had signed a three-year deal with Polydor. A few Chelsea singles came out on Polydor, including Lulu's version of 'The Man Who Sold The World' b/w 'Watch That Man' (2001-4-90; 1/74), which reached the No.3 spot in the Charts, the highest that any Chelsea product was to reach. Chelsea made its appearance as a label proper in April 1974, as part of the Polydor stable. Numbering of its singles, which was in a 2005-000 series, reached 2005-074 by the autumn of 1976, but a lot of the numbers were not used in Britain. As was the case with other Polydor and Phonogram singles, labels were injection moulded (1). The only change in design came at the start of 1976, when the small 'A' at 2 o'clock grew in size (2). Where singles had originated with Roxbury, that fact was mentioned on the labels (1). After the move to Pye, in November 1976, numbering changed to a CHS-3000 series, and paper labels (3), much more colourful than the injection moulded Phonodisc type, were used. Demo labels appeared for the first time; their layouts resembled that used by EMI, for some reason (4) - thanks to John Timmis for that scan. The relationship with Pye proved to be brief and yielded just three singles.

As 'BB' of the 14th of July 1975 had stated, Chelsea enjoyed more than its share of singles success here, for an independent label. During its time with RCA it touched the Top 20 position with New York City's 'I'm Doing Fine Now' b/w 'Ain't It So' (RCA-2351; 7/73). After the Lulu hit on Polydor mentioned above it got three records into the Top Ten and two more into the Top Twenty, Disco Tex & The Sex-O-Lettes (twice), Jim Gilstrap, Dee Clark and Linda Carr & The Love Squad all contributing. Lulu had four singles out on Chelsea, but only 'Take Your Mama For A Ride (Parts 1 and 2)' (2005-037; 4-74) made any impression, peaking at No.37. The final Chelsea singles came out here in May 1977.

Copyright 2006 Robert Lyons.